I spent a great deal of 2023 on Zoom calls with a tribal elder of the North Fork Mono tribe in California: Ron Goode. He is overwhelmingly well-respected in his community, so I’d initially been very nervous to speak with him. And his demeanor in the beginning proved I had reason to worry. He was a bit rough: skeptical, short, serious. It was exactly the kind of treatment you’d expect from someone who didn’t trust you.

For years, I’d been reporting on the climate crisis. And therefore, I’d heard about this ancient Indigenous fire practice that apparently had the potential to fight wildfires, therefore, mitigate the impacts of climate change. They were called cultural burns. Ever since I heard about them, I wanted to know more.

But I knew that if I ever wanted to tell a story about this, it would require a great deal of trust-building. Indigenous communities, like so many other disenfranchised groups, had every reason to close their doors to journalists.

So for many weeks before I uttered a single word to any tribal member, especially Ron, I set out to do what every story requires: a lot of research and a lot of learning.

Through lots of reading and informational interviews, I began to learn about the U.S.’ historically contentious relationship with wildland fire, and how they enacted policies to suppress all kinds of fire for more than a century.

I learned how these policies criminalized Indigenous communities’ use of fire to steward their lands, maintain wildlife habitats, and keep soils and ecosystems healthy.

Eventually, after much damage was done to both our ecosystems and to tribal communities, the U.S. changed course. Partially thanks to wildfires.

It turns out that the U.S.’ era of fire suppression actually made lands more vulnerable and susceptible to the massively destructive wildfires the world is seeing today. Lands actually need fire in order to build resiliency to more fire.

So some states began to put fire back on the land. Agencies called this “prescribed burning.”Much like cultural burns, they involve setting low-intensity fires that benefit ecosystems in a myriad of ways.

However, there are key differences between prescribed burning and cultural burning, both in practice, and, of course, with regards to their cultural significance to tribal communities.

And the extent of those differences have been unfolding in real time in the state of California. Recent legislation has basically grappled with the question of whether the state views both types of burns as equal, and whether cultural fire practitioners have the same rights and protections as prescribed burners to set fire to the land.

And this was the point in my journey where I finally felt ready to talk to cultural burners themselves. The angle of this story had started to emerge.

While there is significant media coverage on prescribed burns, cultural burns, and their benefits to the environment, I hadn’t found much on the impacts that fire suppression had on Indigenous communities on a cultural level.

How did a practice survive after it was taken away for so long? And how were those impacts playing out today, when U.S. policies gave those practices a new life?

Ron was not the first Indigenous person I spoke to. I was introduced to him by Melinda Adams, a San Carlos Apache cultural fire practitioner who’d done a lot of work in this space in California, but was now in Kansas.

She very openly and graciously walked me through their journey. She was patient with my questions. And she was refreshingly honest about the frustrations within her community.

But perhaps more importantly, she guided me through the cultural sensitivities I needed to keep in mind when talking about their right to burn. And she was clear it would be difficult for me to pursue this story. For them, it wasn’t just about a lack of trust for journalists, or for people outside their community—which she warned Ron very much felt. But it was also about their need to protect their sacred knowledge.

There would always be limits to what they would share with me because their knowledge about stewardship and their lands is passed down generation to generation, and has been for millennia. It’s not information they openly share with people outside their communities. Quite the opposite, they safeguard it. In a lot of ways, Melinda helped narrow the distance between me and her community, so I could approach them at the right time in the right way.

I still remember the moment I felt the ice melt with Ron. It took a few tries before our conversations shifted from dry distrust to a more open exchange. The shift happened when he took an interest in knowing more about me. He asked, “So where are you from anyway?”

The story I would end up telling would be about cultural reclamation; how Ron is one of the few people across many tribes who was still taught about cultural burning in secret, despite the risks; and how he and others are leading the way in not only bringing it back, but preserving it for future generations.

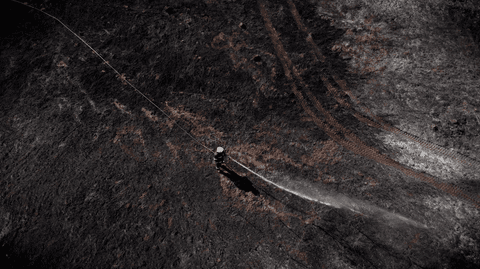

Part of how he does that is by holding his own cultural burn ceremonies several times a year. He invites tribes from all over the country and abroad, but he also invites allies and agencies who are open to learning from cultural burners.

This would be my next challenge. Since I wanted this to be a documentary, I quietly hoped he would invite me to film his upcoming burn in November 2023. But I wasn't optimistic about it. Especially when he told me that he’s invited journalists before, but never invited any of them back. So I didn't dare ask to be invited.

A lot hinged on this relationship with Ron. He’s a tribal elder after all. Even Melinda wouldn’t ever fully trust me until Ron did. They needed to feel that I not only wouldn't misrepresent them or what they're fighting for, but that I would also respect the access to their world, should they open the door to it.

Then one fateful day, he said, “So are you coming or what?”

To watch the full documentary: “The Story of the Right to Fire: Reclaiming Cultural Burns,” head over the News Movement’s Youtube page.